Hoe and Worthing Archive: The Village

|

| Contents Lost village Topography 18th-century maps The Town House and rural poverty Fear of invasion A lost common |

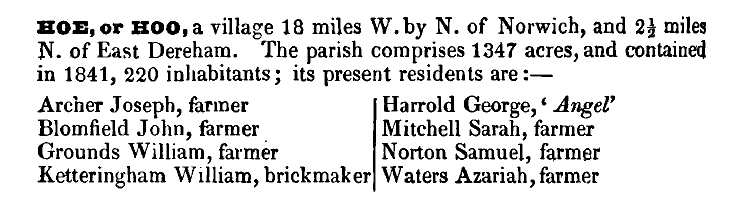

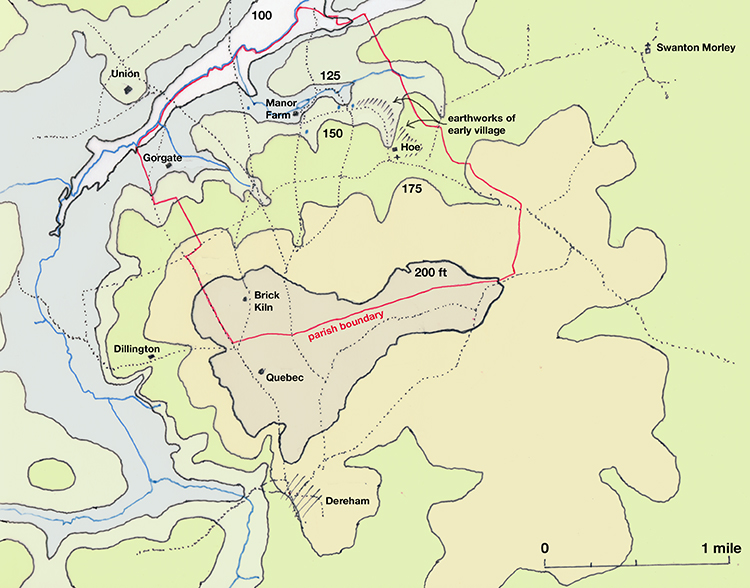

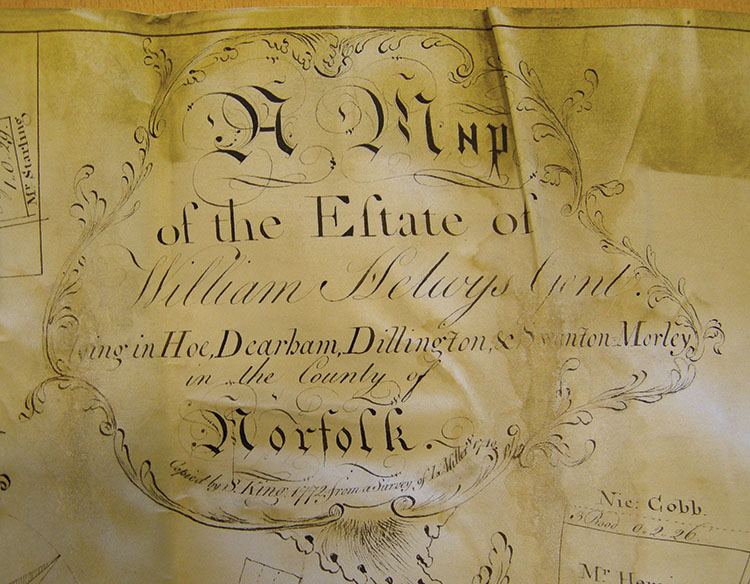

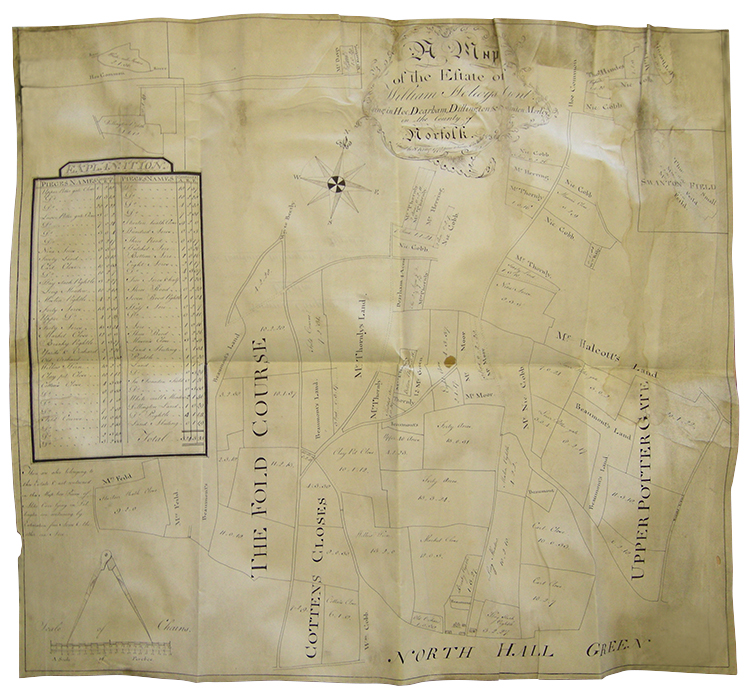

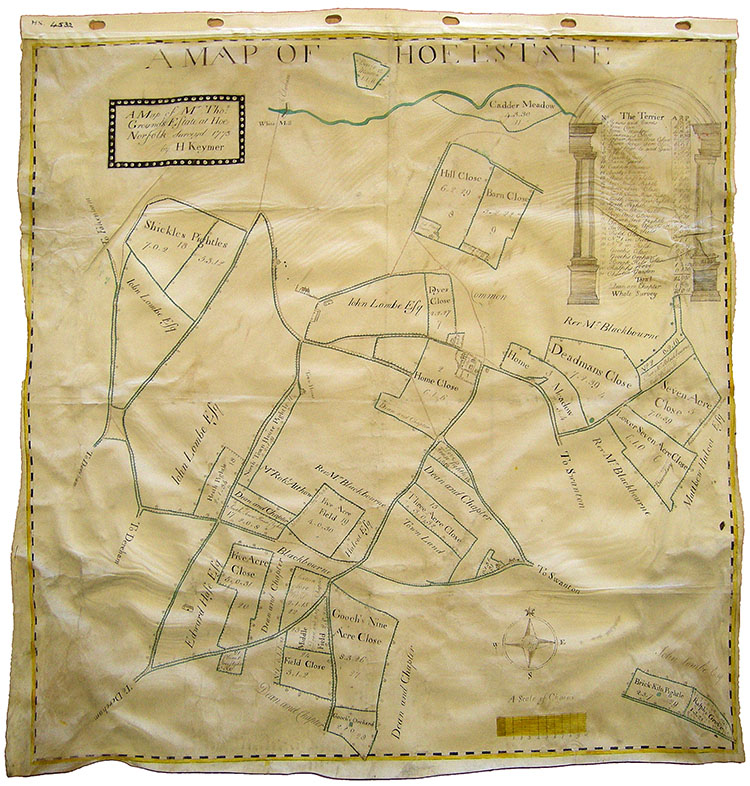

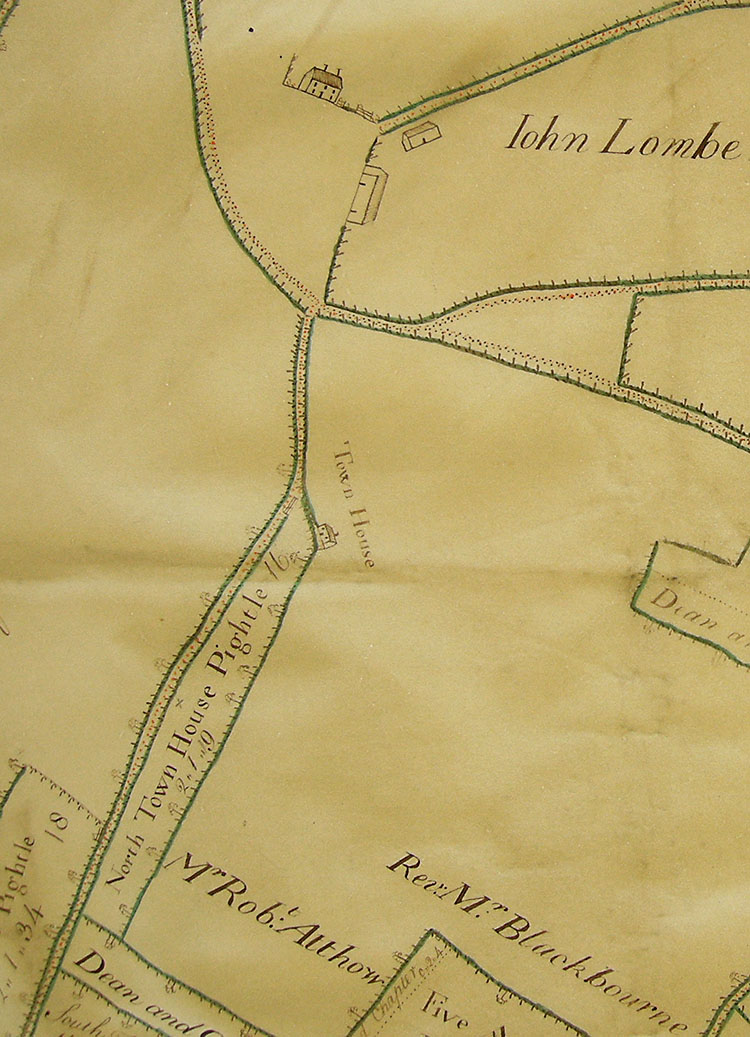

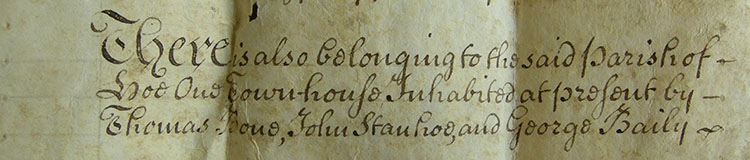

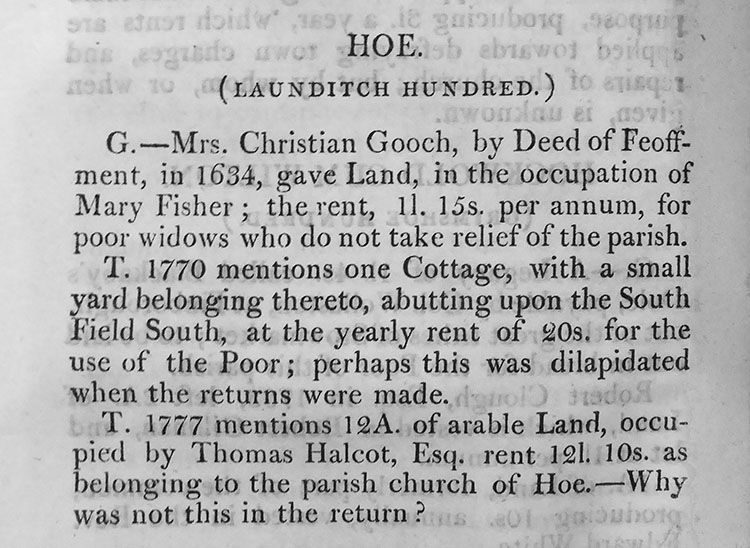

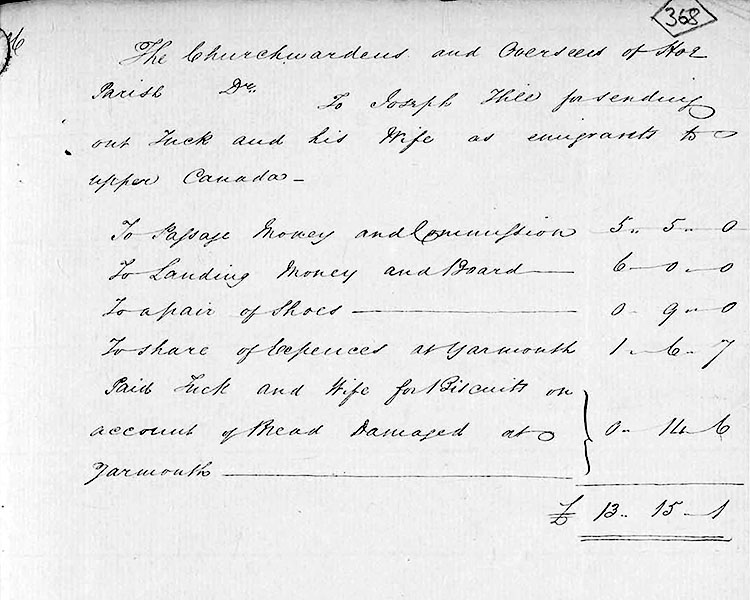

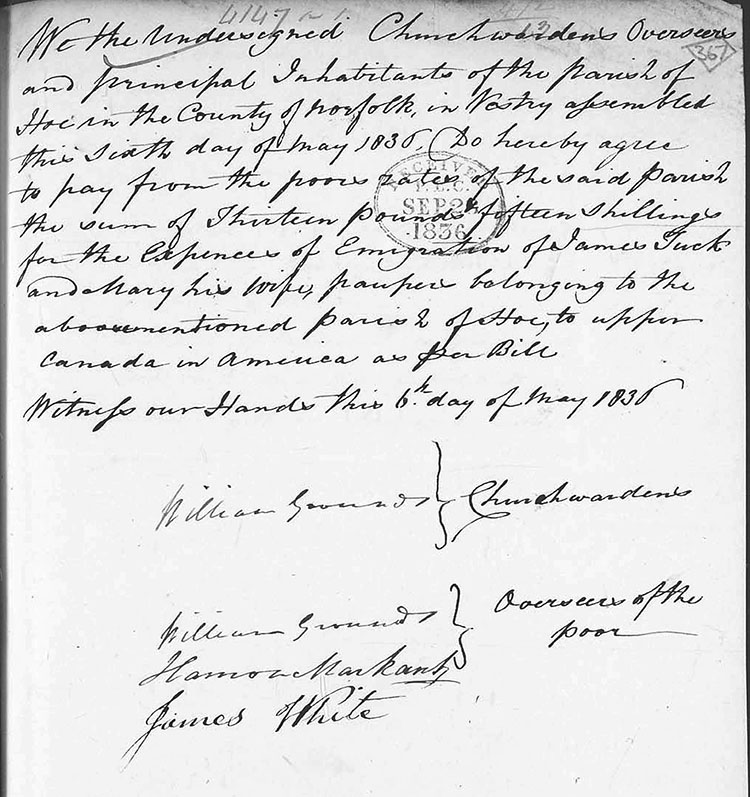

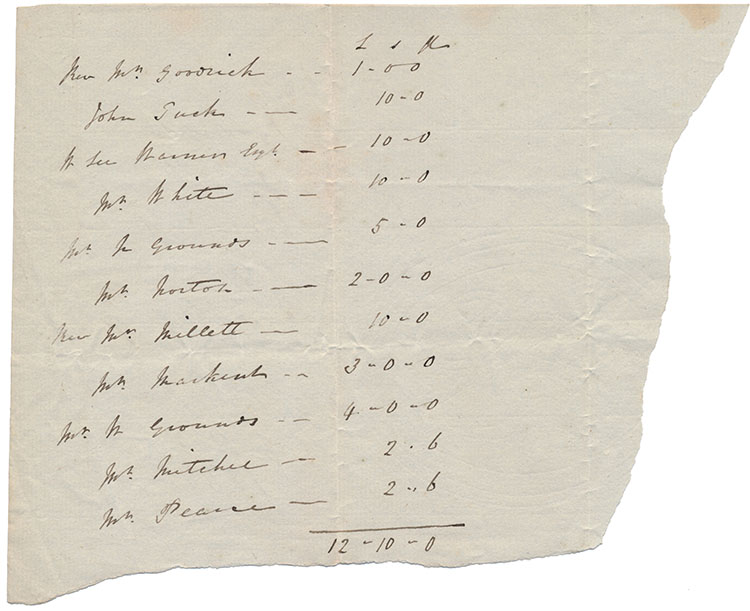

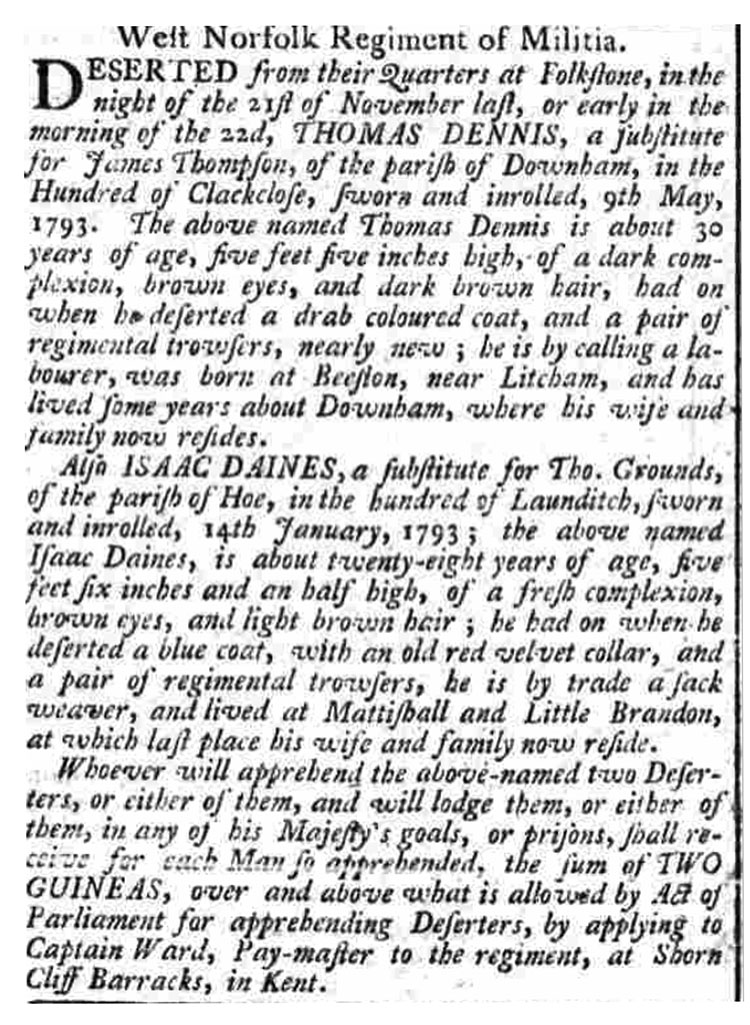

This 1850 trade directory entry gives a partial impression of the sort of place Hoe was in the mid nineteenth century, and most likely had been for a lot of its history. Note the spelling 'Hoo' – that's how most of its inhabitants would have pronounced it. The census of 1841 fills in some of the detail. Of the 220 inhabitants, sixty-two were agricultural labourers (a third of whom were under eighteen years old). Including their families, a total of 137 – over half the population. There was a schoolmistress, but schooling wasn't compulsory until 1873, and so children of labourers would have been more likely to have been working on the land than being taught to read and write. In 1841 an agricultural labourer in Norfolk would have earned about eight shillings a week, supplemented by whatever smaller amounts his wife and children could earn. Eighteen inhabitants were female servants and there were three shoemakers, the only tradesmen apart from the brickmaker. At Gorgate Hall, William Millett, a curate at Swanton Morley, employed a governess, one male and four female servants and a gardener. The game laws enacted to discourage poaching required the purchase of a licence to shoot game. In 1830 two Hoe residents held them, both members of the Grounds family, at a cost each of £3.13s.6d (Norfolk Chronicle 2.10.1830).  Faden's map of Norfolk of 1797 shows Hoe as a small settlement off the main road. Some buildings are recognisably still with us, others are not, including the windmill on the Common. The brick kiln on Stanton Heath was still active in 1917 when the Bylaugh estate was sold. [Reproduced by courtesy of Andrew Mcnair.]  A part of the estate map of Thomas Grounds, 1772, shows the common extending into the centre of the village. [Courtesy of Norfolk Record Office MS 4532] Lost village  This aerial photograph was taken in 1946 by the RAF. In the centre at the bottom, at the road junction, are the church and hall; north of them, extending round the bend in the road, can be seen rectangular indentations and other earthworks. They mark the site of a part of the village abandonded or displaced, probably in the medieval period. The line of what may have been a road can also be seen curving sharply to the north-east (centre right) to join the present road to Swanton Morley. The earthworks include several moated enclosures and a mound on which a windmill may have stood. [Copyright Norfolk County Council; photo by RAF 31 January 1946] A complete record of archaeological surveys of the site is available at http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?MNF2810-Earthworks-of-the-shrunken-medieval-settlement-of-Hoe&Index=2&RecordCount=1&SessionID=97877579-dc73-422b-a21c-2120b2f2bbde Other aerial photos of the site, from the Cambridge University collection, taken in February 1970, can be seen at: http://www.cambridgeairphotos.com/location/bat48/ Historic England's website has aerial photographs of he site taken in 2008. https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/archive/collections/aerial-photos/  In 2008 vehicle erosion of the roadside bank near the deserted village site exposed these remains of a flint-faced wall, possibly medieval. Topography The name Hoe means a hill. The Oxford English Dictionary references a 15th-century source describing Stanhoe, also in Norfolk, as a stony hill. But Hoe isn't obviously perched on a hill and the slope from the village down to the north of the parish is a gentle 25-50 feet. Nearer Dereham, however, there is a fall of almost 100 feet in less than half a mile. The area is no longer in the modern parish of Hoe, but historically, according to Boston & Puddy's Dereham, Hoe was part of that parish. Perhaps that slope gave the area its name.  [Based on Ordnance Survey data, PSMA licence number: 0100053823] 18th-century maps Two estate maps of Hoe are held in the Norfolk Record Office. Both are of private land holdings in the late eighteenth century. They give the names of other landowners as well as some field names.  This map is dated 1772, based on a survey of 1740. Perhaps the lands had been in the Helwys family all that time. The 'Explanation' of the holdings lists 324 acres in total. William Helwys was a Norwich resident from a prominent family who included three Mayors, in 1683, 1684 and 1713. [Courtesy of Norfolk Record Office CHC 11901]   This map shows the estate in Hoe of Thomas Grounds, surveyed in 1773. Drawn on vellum by H. Keymer, it lists the names of the fields with their acreages, and the names of owners of adjacent land. Interestingly, it does not show either the church or the hall, where the family later lived. Home Close, at the centre of the map, is adjacent to Angel Farmhouse, numbered 1 in the Terrier. Perhaps Grounds lived at the farmhouse there at the time.  The surveyor was ‘… Henry Keymer of East Dereham of whose output some half-score maps survive. He also dealt in second-hand books as well as teaching “The English Language, Writing, Arithmetic, Book-keeping, Surveying, Plotting and Mapping of Land, Algebra, The Use of the Globes" and so on. His schoolroom was used by him for periodic auctions at which he sold "Stationery … Sheffield and Birmingham Cutlery Ware, English and Dutch Toys” and a variety of other commodities and knick-knacks. A generation later, in 1790, he is advertising “Herring's Norfolk Antidote … for the Bite of Mad Dogs and Other Mad Animals”… . Keymer died in 1807 in his 85th year.’ [Courtesy of Norfolk Record Office MS 4532] The Town House and rural poverty  The Grounds estate map also shows the 'Town House' on Barkers Lane. At the top here is Manor Farm. Before the building of the Poor Law institutions like Gressenhall House of Industry (Mitford & Launditch Hundreds Incorporation, 1776), provision for people unable to support themselves through age or infirmity was made locally. The rent from the adjacent pightle perhaps went towards paying for their keep. [Courtesy of Norfolk Record Office MS 4532]  Thomas Bone, John Stanhoe and George Baily lived at the Town House according to this eighteenth-century terrier. [Courtesy of Norfolk Record Office DN/TER 86/1/?]  This is the entry for Hoe in Zachary Clark's 1811 An Account of the Charities belonging to the Poor of the County of Norfolk abridged from the Returns under Gilbert's Act, to the House of Commons in 1786; and from The Terriers in the Office of the Lord Bishop of Norwich. T (for terrier) of 1770 describes a cottage for the use of the poor. Its position, abutting upon the South Field South, presumably refers to one of the open fields of Hoe, much of which had already been enclosed at this date. If the survey 'returns' dated from 1786, then the Gressenhall Union would have superceded this parish house, hence the dilapidation. Manor Farm cottages on Barkers Lane probably contain the remains of the Town House. See Manor Farm page http://www.hoeandworthingarchive.org.uk/manor_farm.html Manor Farm Cottages.  The Poor Law could lead to disputes between parishes. A person who became destitute could only apply for support from the parish in which he or she had a settlement, and poor people were often shunted from one place to another to in an effort to reduce parish rates. This court case between Hoe and Thursford found in favour of Hoe and the parish was recommended to send the paupers back to Thursford. No mention is made of who they were. Norfolk Chronicle 18th May 1776 Rural poverty was frequently extreme in the mid nineteenth century owing to a combination of low wages, poor harvests and the impact of the Corn Laws which held the price of staple foods artificially high until their repeal in 1846. In the 1820s, ’30s and ’40s outbreaks of rural unrest were common in East Anglia, farm labourers protesting against low wages, the price of food and unemployment. They often resulted in machine breaking or arson. Horse powered threshing machines were a common target of protesters. Employment in the winter months for labourers mostly depended on threshing corn by hand, with flails, a slow job. Farmers threatened with machine breaking often agreed to suspend their use. Those that didn’t could suffer the fate of Mr Hart, of Hoe: On Saturday last, a large body of labourers assembled at Lyng, to the number of 300 or 400, and forced the door of the paper mill and broke the machines for making paper therein, and did other damage to the amount of £800. From thence they proceeded to Mr Hart’s of Hoe, where they broke his threshing machine, etc., and from thence to Billingford where they destroyed two threshing machines.Norfolk Chronicle 27th November 1830 “Malicious burning of Houses or Property, and the destruction of Machinery” carried the death penalty. A record preserved in the National Archive [MH_12_8474_165_1] reveals that James Tuck and his wife Mary were paupers resident in Hoe who emigrated to Canada in 1836. The emigration of poor people was overseen by the Poor Law Commission set up in 1834 to apply the new law, governing workhouses including the Mitford & Launditch Union at Gressenhall. Immigration to northern factory towns or emigration to British colonies were promoted as ways of achieving reductions in the poor rates paid in the countryside principally by landowners and employing farmers. There were times of severe economic hardship and unemployment throughout the first half of the 19th century. Parishes were allowed to pay emigration expenses from the poor rates if approved by the Commission. Emigration from Norfolk parishes in 1836 accounted for almost three fifths of the national total, at a cost of £15,198. [Source: https://www.workhouses.org.uk/emigration/] James and Mary Tuck were given the following allowances for their journey:  To Passage Money and Commission 5. 5. 0_________ £13. 15. 1 _________  William Grounds of Hoe Hall was Churchwarden and one of the Overseers of the Poor whose job it was to collect the poor rate and disburse it. This a Minute from the Parish Vestry meeting dated 6th May 1836.  This

scrap of paper in

the handwriting of

William Grounds of

Hoe Hall lists the

subscribers to a

'Dinner for the Poor

of the Parish of Hoe

1838' celebrating

Queen Victoria's

coronation. The

subscribers were

local gentry, clergy

and farmers including

William and another

member of the

Grounds family.

John

Tuck

subscribed ten

shillings –

not all of the

Tucks were

paupers. This

scrap of paper in

the handwriting of

William Grounds of

Hoe Hall lists the

subscribers to a

'Dinner for the Poor

of the Parish of Hoe

1838' celebrating

Queen Victoria's

coronation. The

subscribers were

local gentry, clergy

and farmers including

William and another

member of the

Grounds family.

John

Tuck

subscribed ten

shillings –

not all of the

Tucks were

paupers. Fear of an invasion The wars against France (1793-1801, 1803-15) caused consternation along the east coast from Norfolk to the south coast. Napoleon was known to be planning to invade Engand and the estuaries and beaches, particularly of Suffolk and Essex, were thought to be the most likely landing places. Amongst other measures aimed at mobilising the country's resources, people who owned horses and transport were required to 'provide and furnish' them to the military 'at the shortest notice, without any recompense whatever'. T C Munnings (Gorgate Hall, rector of Beetley and East Bilney), Edward Blyth (Manor farm) and Thomas Grounds (Hoe Hall) subscribed. Because the French Revolution aroused republican feeling in East Anglia and prominent Norfolk Whig politicians like Thomas Coke of Holkham opposed the war, taking part in this scheme would have seemed a loyal act by supporters of Pitt's government.   The war with France persuaded the government to ensure that the militia regiments, including the Norfolk, founded in 1757, were fully manned to face the renewed threat. Cities, boroughs and hundreds were required to supply certain numbers of men; Launditch hundred, which included Hoe, had to provide twelve. Men enlisted, such as Thomas Grounds of Hoe Hall, could pay for substitutes to serve in their stead. Norfolk Chronicle 3 December 1796  Isaac Daines was Thomas Grounds' substitute but absconded after three years in the militia. Deserters faced severe punishment such as flogging if caught. Norfolk Chronicle 3 December 1796 East Anglia against the Tricolour, 1789-1815, by Julian Foynes, Poppyland Publishing, 2016, gives a fascinating account of the wider effect of the conflict on the region. A lost common  [Courtesy of Norfolk Record Office C/Sca/2/243]  Hoe once had another common, called

Northill Common

Hoe once had another common, called

Northill Common on Faden's map of 1797. It was over a mile wide and was shared with Dereham. The Hoe part is the funnel-shaped area outlined in pink on the enclosure map above (above the words Parish Boundary, No.76). Faden's map shows several roads converging on the common and houses grouped along its southern boundary. The land was enclosed and allotted to the Dean & Chapter of Norwich Cathedral who already had extensive land holdings in Hoe, as the map shows. [Reproduced by courtesy of Andrew Mcnair.] The Norfolk Heritage Explorer website lists all the known antiquities in the village: http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?TNF276-Parish-Summary-Hoe-%28Parish-Summary%29 |